Issue 19: Darkest Before the Dawn

Hey there!

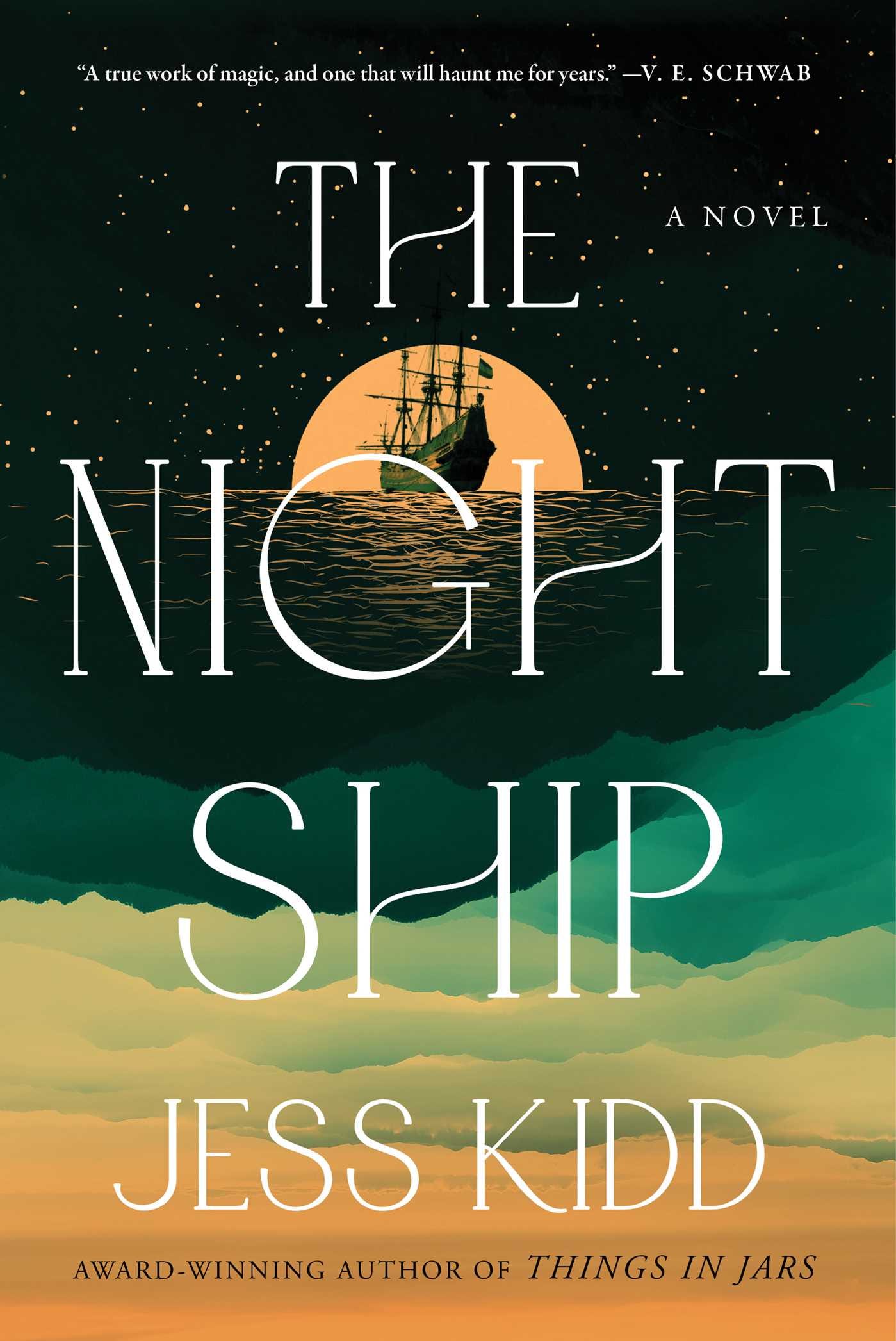

Better late than never! At the very end of another year, it’s time to go big, discussing works that are excessive in the best way–dramatic, sweeping, emotional, and full of well-crafted angst. If you’re looking for catharsis as we steer into 2023, a ghostly shipwreck novel and Taylor Swift’s latest album will more than deliver. Alex reviews The Night Ship and Claudia praises the confessional lyricism of Midnights.

Alex on The Night Ship

“The Batavia story is not really for kids,” a kindhearted sailor warns protagonist Gil midway through Jess Kidd’s latest novel. Gil shoots back: “But there were kids in the story, weren’t there? Kids on the ship and kids getting killed?” His stubborn, prickly brand of clear-sightedness grows out of the tragedies that have shaped his life. It also enables Gil to confront the historical tragedy haunting the remote island where he’s been sent to live with his surly grandfather. He innately understands what decent adults really struggle to grasp, that horrible things happen to kids all the time. Evil doesn’t discriminate based on age.

The Night Ship is a grim book and a sad book. It’s chilling and magical, full of sweeping adventure and creepy folklore. It’s a ghost story; it’s not really about survival but about endurance, and the imprints (sometimes malignant, sometimes just lonely) that tragedy can leave on a landscape. Very technically it’s a time-slip novel. Really it’s full of time-echoes.

Split timelines alternate between Mayken, a girl sailing on the Dutch East India Company’s flagship Batavia in 1628, and Gil, all but stranded on Australia’s Beacon Island in 1989. For the most part, their storylines parallel each other rather than intersecting.

Beacon Island—or Batavia’s Graveyard—is a coral island that survivors made their way to after the ship was wrecked on a reef. Mayken scrounges for food and shelter as the nightmare spirals. Merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz takes control, first hoarding weapons and provisions, then manipulating, enslaving, and murdering other survivors. Hundreds of years later, the island is still steeped in isolation and malice. Gil struggles to connect with his grandfather, who’s awkward in his best moments and cruel in his worst. A feud with a neighboring family boils over. Gil becomes the target of fresh violence.

There’s a lot going on here, and The Night Ship can be clunky in ways that novels which utilize split timelines often are. Both storylines are compelling, but you’ll probably prefer one over the other (it’s the 1600s shipwreck horror for me). Of the constant parallels between Mayken and Gil, some are developed better than others. For example, both characters crossdress, but Mayken’s need for a disguise that will allow her to penetrate the Batavia’s belowdecks underworld gets much more attention than Gil’s urges and uneasiness with his sexuality.

Still, this book retells a historical tragedy—one of the worst in maritime history—in a way that gets at its pointless brutality without tipping over into complete hopelessness. It’s no spoiler to say that Mayken doesn’t survive (in Gil’s time islanders leave offerings to the ghostly Little May), but again, The Night Ship is about endurance, not survival. Mayken’s ghost haunts the island, but Mayken herself is still somehow present—she and Gil brush up against each other in fleeting, inexplicable ways. Endurance goes beyond survival. It sinks its roots deeper. In The Night Ship, endurance is both the impact of history on a landscape and the impact of one person on another person’s life.

It’s a connection forged against all odds. It’s transcendent.

Back to Gil, who more than any other character bears a sense of responsibility towards the past. He hints at it when he argues about the Batavia’s story. History can be respected or it can be grappled with, but it can’t really be exorcized. Children were murdered, and brutally, on Beacon Island. They were real people, with tangled, imperfect lives very similar to Gil’s, and on some level he understands that he has to respect and connect with them in order to save himself. They were real people. Horrible things were done to them, but they endured. So can he.

Claudia on Midnights

Taylor Swift’s music was such an integral part of my messy, embarrassing adolescence, that, unlike a lot of artists I liked at eleven years old, I’ve continued to listen to her. Part of the appeal of growing up alongside her music is being able to map her development as an artist alongside my own increasingly complex experiences as a preteen, teenager, and adult.

In her latest album, Midnights, Swift’s lyrics grow in emotional depth, but her thematic preoccupations—romantic and interpersonal relationships, identity, and anxiety—remain steady. These are typical preoccupations for teenagers, but her songs are also intensely relatable for listeners who, while no longer adolescents, still feel the same uncertainty associated with their younger selves. In Midnights, Swift continues bridging the gap between her teen and her adult audiences by showing the parallel emotions connecting youth and experience.

If the album has a thesis statement, it’s the opening lines of “Anti-Hero,” “I have this thing where I get older but just never wiser.” Swift writes that the track confronts her “struggle[s] . . . with the idea that my life has become unmanageably sized,” and while this comment seems to reference the nature of celebrity, it also reminds me of more day-to-day stressors: the simmering, hormone-influenced overload of my early teens, and the overwhelm of learning to juggle a job, house, and car payments in my early twenties. The idea of setting a firm boundary between the adolescent and adult emotions is appealing, probably because teenagehood is such a terrifyingly nebulous time, but the truth is that the intensity I felt as a thirteen-year-old hasn’t gone away. It’s just attached itself to new fears, and often resurrects old ones. Another of my favorite tracks, “Question. . .?” taps into this whiplash by contrasting hoped-for kisses with “ politics and gender roles / And you’re not sure and I don’t know.” The emotions I associate with teenage immaturity and melodrama don’t pass with age—instead, they mix uneasily with the worries I deal with now. Listening to Swift allows me to link my current fixations with the ones I developed as a child, whether that’s through the tortured romance of “Midnight Rain” or the suburban trauma of “You’re On Your Own, Kid.”

When I was about fifteen, my mom told me that the big secret of being an adult was that I would feel the same when I grew up as I did now. Learning to process the emotional peaks and valleys of adolescence and beyond is not moving away from feelings of pain and inadequacy, but taking responsibility for them. Midnights, insistent and confessional in a cultural landscape that often mocks both of those things, does just that.

There’ve been some bumps along the way, but we’ve kept this tiny newsletter chugging along for another year and hope to keep it up in 2023. See you then, and thank you, as always, for reading!

Till next time,

Alex and Claudia